Reflexive Verbs In Spanish: The Only Guide That You Need

Get our free email course, Shortcut to Conversational.

Have conversations faster, understand people when they speak fast, and other tested tips to learn faster.

More infoReflexive verbs in Spanish can be tricky to learn, and even more difficult to adapt naturally into your conversation. Mastering them is an important step in becoming a competent speaker, so we bring you this updated guide to show how and when to use reflexive verbs in Spanish.

For example, the verb “lavar” simply means “to wash,” but once you add “-me” to the word and it becomes “lavarme,” now I’m washing myself. Simple? Well, not quite.

The reality is that reflexive verbs are used constantly in Spanish, and you need to master them to sound like a native, which may take time. But here’s the upside: once you get the hang of them, half of everyday Spanish—waking yourself up, calming down, even congratulating each other—comes together easily.

What is a reflexive verb in Spanish?

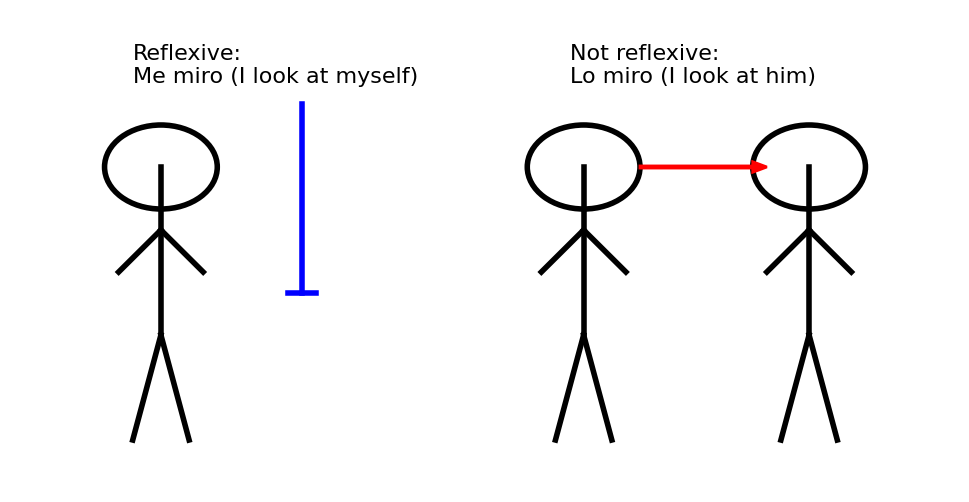

A reflexive verb (“verbo reflexivo”) is a verb where the subject and the object are the same person or thing.

In other words, the action reflects onto the subject.

If I am both the doer and receiver of an action, that verb is reflexive.

For example, I wake (myself) up, he gets (himself) dressed, she showered (herself), and so on.

The reflexive pronouns in Spanish

In Spanish, you can easily spot a reflexive verb in its infinitive form by the special “-se” ending attached to it, which is a reflexive pronoun:

- lavarse

- mirarse

- preocuparse

However, that’s not the only one.

Every Spanish reflexive verb is paired with a reflexive pronoun.

These pronouns indicate “to whom” the action is happening when it’s self-directed.

Essentially, they mean myself, yourself, himself/herself/itself, ourselves, yourselves, or themselves.

Here are the Spanish reflexive pronouns, which correspond to the subject of the sentence:

| Reflexive pronoun | English meaning | Subject pronouns |

| me | myself | yo |

| te | yourself | tú |

| se | himself / herself / itself / yourself (formal) | él, ella, usted |

| nos | ourselves | nosotros / nosotras |

| os | yourselves (Spain) | vosotros / vosotras |

| se | themselves / yourselves (formal plural) | ellos, ellas, ustedes |

🌎 Note: Spain uses the informal vosotros, but nearly all Latin American countries use ustedes for every plural “you.” Keep this in mind when using the reflexive pronoun “os” (informal plural in Spain) or “se.”

Where to place Spanish reflexive pronouns in a sentence

A good example is “lavarme“. “-me” implies that I’m washing myself. It’s written at the end, and that becomes reflexive.

However, the general rule is that the pronoun comes before the conjugated verb, but there are important exceptions when using infinitives, gerunds, or commands. Let’s break down the placement rules:

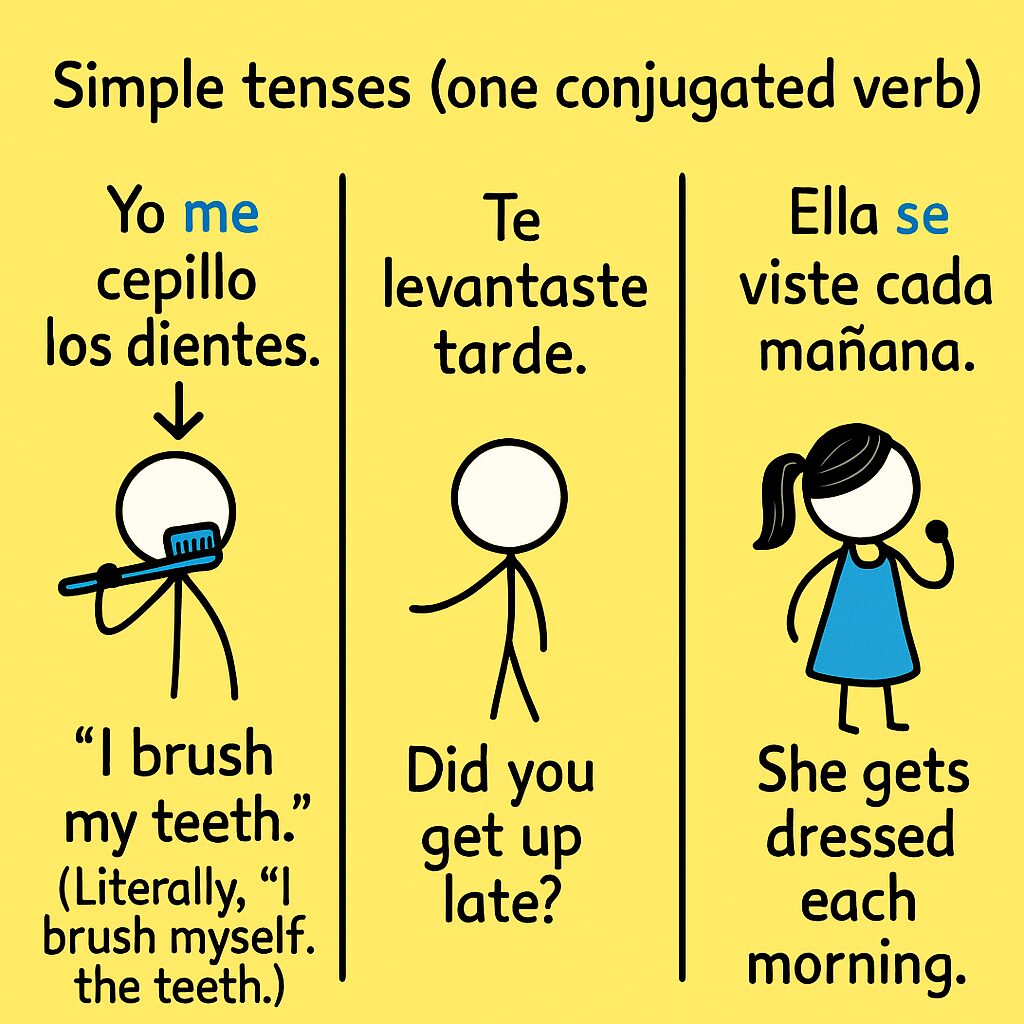

Simple tenses (one conjugated verb)

Put the pronoun immediately before the verb.

- Yo me cepillo los dientes. – “I brush my teeth.” (Literally, “I brush myself the teeth.”)

- ¿Te levantaste tarde? – “Did you get up late?” (This can also be an affirmative sentence, without the quotation marks)

- Ella se viste cada mañana. – “She gets dressed each morning.”

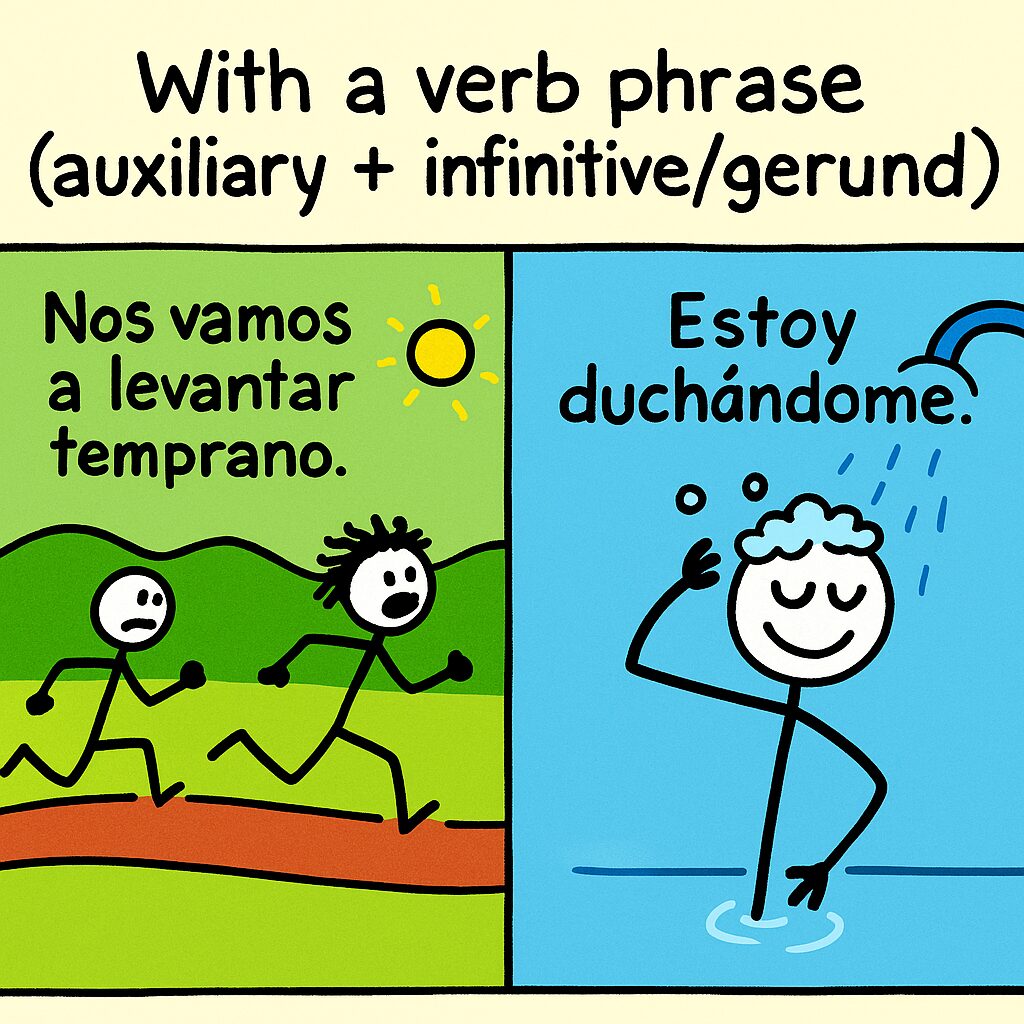

With a verb phrase (auxiliary + infinitive/gerund)

You often have a conjugated helping verb plus an infinitive or gerund (e.g. ir a, estar + -ando/-iendo, or haber + participle).

In these cases, you have two options:

- Place the pronoun before the conjugated auxiliary verb, or

- Attach it to the end of the non-conjugated form (the infinitive or gerund).

For example, “We are going to wake up early” with levantarse temprano:

- Nos vamos a levantar temprano. (pronoun before conjugated vamos)

- Vamos a levantarnos temprano. (pronoun attached to the infinitive levantar)

Both are correct and mean the same thing.

Another example with a gerund (present progressive): “I’m showering” can be:

- Me estoy duchando. (pronoun before estoy)

- Estoy duchándome. (pronoun attached to duchando

Remember: When attaching to a gerund (the -ando/-iendo form), remember to add an accent to maintain the original stress of the gerund. E.g. duchándome, vistiéndote, durmiéndose.

Affirmative commands

For positive commands, Spanish attaches the pronoun to the end of the verb. Think of it as one word.

- ¡Levántate! – “Get up!” (literally “raise yourself!”)

- Siéntense, por favor. – “Please sit down.” (to a group: “seat yourselves”)

Note: This last sentence is either used in a formal context in Spain or in most Latin American countries. European Spanish would use “sentaos, por favor” for the informal plural.

Same thing as before, whenever you attach a pronoun to a command, if the resulting word has more than three syllables, add an accent to keep the stress.

Negative commands

For negative commands, the pronoun goes before the verb (and after the “no”).

- ¡No te levantes! – “Don’t get up!”

- No se preocupen. – “Don’t worry (you all).”

“No” in regular sentences

In any normal sentence (not a command), if you’re saying something negative, the word “no” comes before the reflexive pronoun. For example:

- No me ducho a la tarde. – “I don’t shower in the afternoon.” (No + me + verb)

- Ellos no se quieren ir. – “They don’t want to leave.” (No + se + conjugated verb)

To sum up, the pronoun before the conjugated verb is the default.

If you have infinitives or gerunds, you get the flexibility to attach them, and commands have their own special rules (attach for positives, place before for negatives).

After some practice, this will feel natural. It will become a reflex, so to speak!

When and how to use reflexive verbs in Spanish

OK, but when and how will you use reflexive verbs in Spanish exactly?

Here are some situations I can think of:

Daily routines

If there have been many examples of daily routines in this article, it’s because reflexive verbs are common to personal care or everyday actions. More examples:

- despertarse (to wake up [oneself]) vs. despertar (to wake [someone] up)

- levantarse (to get up) vs. levantar (to lift/raise something)

- ducharse (to shower oneself) vs. duchar (to shower someone, e.g., bathe a child)

- vestirse (to get dressed) vs. vestir (to dress someone else)

- cepillarse [el pelo/los dientes] (to brush one’s [hair/teeth]) vs. cepillar (to brush something, e.g., a horse, or someone’s hair)

- afeitarse (to shave oneself) vs. afeitar (to shave someone)

- lavarse [la cara, las manos] (to wash oneself [face, hands]) vs. lavar (to wash something/someone)

Remember: When using reflexive verbs for body parts or clothing, Spanish uses the definite article (el, las, los, las) rather than a possessive.

Emotions

Spanish often uses reflexive verbs to describe changes in emotions or states.

Basically, you can use them when someone “gets” or “becomes” a certain way:

- alegrarse – to become happy/glad (Me alegro de verte. – I’m glad to see you.)

- enojarse – to get angry (enfadarse is more common in Spain)

- preocuparse – to worry (literally “to preoccupy oneself”)

- asustarse – to get scared/frightened

- cansarse – to get tired

- aburrirse – to get bored

- sentirse + [adjective] – to feel (an emotion/health state) – me siento nervioso (I feel nervous)

Reciprocal actions

Reflexive pronouns are used with things people do to one another:

- Nos abrazamos. – We hug each other.

- Mis amigos se ayudan cuando estudian. – My friends help each other when they study.

- Ustedes se conocen bien. – You (pl.) know each other well.

- Nos contamos todo. – We tell each other everything.

- Ellos se miraron y se sonrieron. – They looked at each other and smiled at each other.

Verbs that change meaning when used reflexively

A large number of Spanish verbs have both a non-reflexive form and a reflexive form, with sometimes different meanings.

In many cases, adding “-se” can wholly or slightly change the nuance of the verb:

| Non-reflexive verb | Meaning | Reflexive verb | Meaning |

| llamar | to call (someone/something) | llamarse | to call oneself / to be named (Me llamo Carlos) |

| ir | to go | irse | to go away / leave (Me voy) |

| poner | to put | ponerse | to put on (clothing); to become (ponerse enfermo, ponerse triste) |

| dormir | to sleep | dormirse | to fall asleep |

| perder | to lose | perderse | to get lost; to miss out on something |

| volver | to return, come back | volverse | to turn/become suddenly (volverse loco) |

| encontrar | to find | encontrarse | to find oneself (in a place/state); to meet by chance |

| acercar | to bring/move something closer | acercarse | to get closer / approach |

| quedar | to remain; to arrange to meet | quedarse | to stay / remain (oneself) |

| negar | to deny | negarse | to refuse |

| acordar | to agree / decide | acordarse (de) | to remember |

| fijar | to fix, set | fijarse (en) | to notice (¿Te fijaste en…?) |

| parecer | to seem / appear | parecerse (a) | to resemble / look like (someone) |

| comer | to eat | comerse | to eat up, devour completely |

Conclusion

Reflexive verbs might look like grammatical traps at first glance. By now, you’ve seen that they’re just the everyday way Spanish lets the action bounce back to the speaker.

My recommendation is to learn the six little pronouns, memorize where they sit (before verbs, glued to infinitives/gerunds, tacked onto positive commands), and the rest is pure muscle memory.