Present Subjunctive Spanish: A Complete Beginner-Friendly Guide

Get our free email course, Shortcut to Conversational.

Have conversations faster, understand people when they speak fast, and other tested tips to learn faster.

More infoThe Spanish present subjunctive might seem like a grammar monster that everyone warns you about. But don’t worry! In this guide, we’ll clear up the mystery of the Spanish present subjunctive (el presente de subjuntivo). We’ll explain what it is, when to use it (hint: think wishes, doubts, and emotions), how to form it, and provide easy examples so you can better understand it. By the end, the present subjunctive in Spanish won’t seem so scary. Let’s get started!

What is the present subjunctive in Spanish?

The Spanish present subjunctive is not a tense; it is a mood that Spanish speakers flip on whenever they talk about things that are uncertain, desired, doubted, emotionally charged, or dependent on something else.

Think of it as the language’s way of adding a “maybe” filter.

- Indicative (fact):

Pedro está aquí. – Pedro is here. - Subjunctive (wish):

Espero que Pedro esté aquí. – I hope Pedro is here.

That little change from está to esté tells listeners, “Hey, I’m not sure this is real yet.”

English also owns a dusty subjunctive (“I insist that he be on time”), but we use it so rarely that most native speakers never notice it.

Spanish, on the other hand, drops subjunctive forms dozens of times a day. Learning to recognize the mood—and why it appears—will skyrocket your listening and speaking skills.

If the indicative is your favorite news reporter stating pure facts, the subjunctive is your imaginative friend day-dreaming about what might happen. Same mood, different vibe!

How to form the Spanish present subjunctive

Now let’s get practical: how do we cook up a present subjunctive verb form?

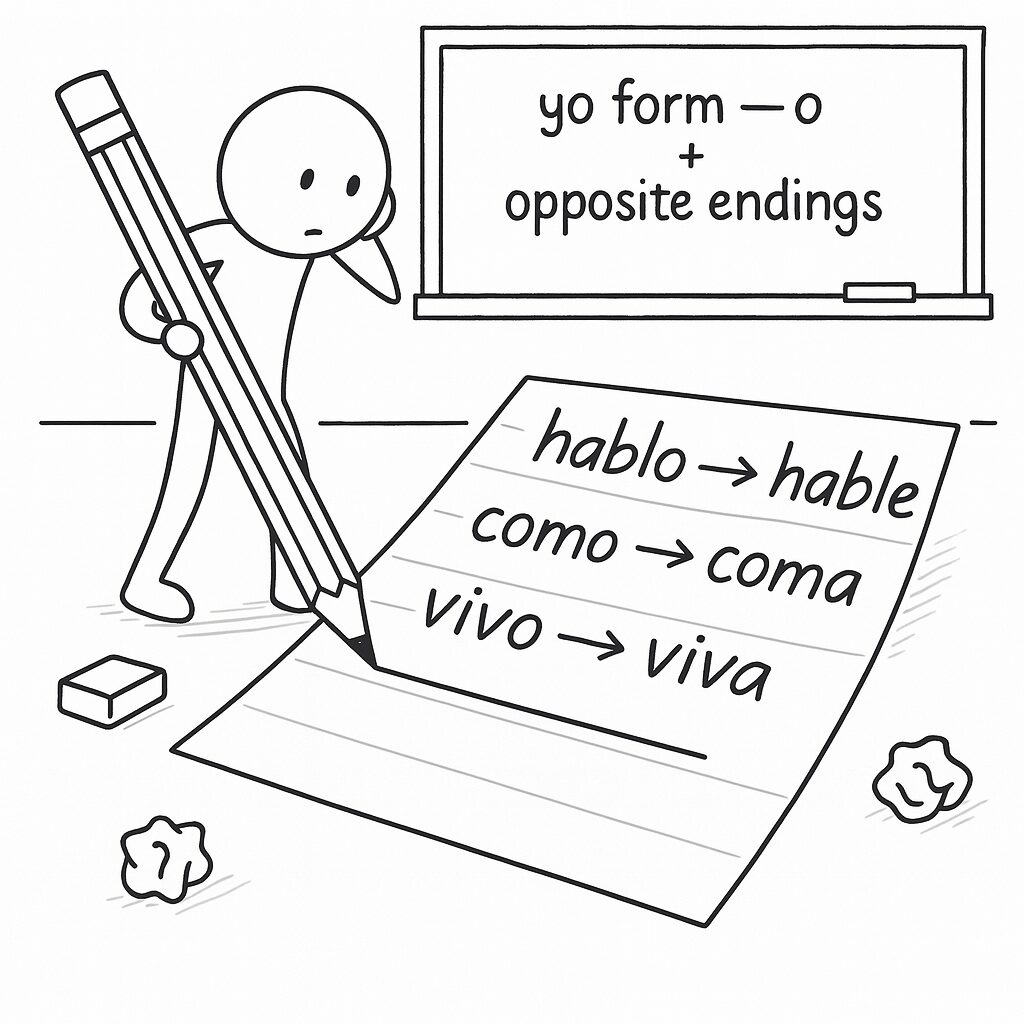

Luckily, it follows a simple recipe. In true Spanish fashion, it mostly comes down to flipping some endings. Here’s the basic formula:

- Start with the “yo” form of the present indicative (the normal present tense yo form of the verb). Hablar (to speak), the yo form is hablo; for comer (to eat) it’s como; for tener (to have) it’s tengo.

- Chop off the “-o.” Literally drop the final -o from that yo form. This gives you the base, or stem, for the subjunctive. (Think of it as removing the old hat from the verb.)

- Add the “opposite” set of endings. This is the fun part: you give the verb a new hat by adding subjunctive endings. By “opposite,” we mean: verbs that normally end in -ar will take the -er/-ir endings, and verbs that end in -er or -ir will take the -ar endings.

Here are the present subjunctive endings at a glance:

| Person | -AR endings | -ER/-IR endings |

| yo | -e | -a |

| tú | -es | -as |

| él/ella/usted | -e | -a |

| nosotros/nosotras | -emos | -amos |

| vosotros/vosotras | -éis | -áis |

| ellos/ellas/ustedes | -en | -an |

Yes, you read that right. -ar verbs use “e” vowels, and -er/-ir verbs use “a” vowels in their endings.

It feels weird, but it’s actually pretty straightforward once you get used to it. Think of it as verbs dressing up in each other’s clothes for a costume party.

Let’s apply the recipe with a regular verb example.

Example 1: hablar (“to speak” – an -ar verb):

- Yo form in present: hablo. Drop the -o → stem = habl-.

- Add opposite endings (since hablar is -ar, we use -er style endings):

- yo hable, tú hables, él/ella hable, nosotros hablemos, vosotros habléis, ellos hablen.

- “Que yo hable” literally means “that I speak” in a subjunctive context. For example, Mi amigo quiere que yo hable – “My friend wants me to speak.”

Example 2: comer (“to eat” – an -er verb):

- Yo form: como. Drop -o → stem = com-.

- Add opposite (-ar type) endings:

- yo coma, tú comas, él coma, nosotros comamos, vosotros comáis, ellos coman.

- e.g. Es importante que comas verduras – “It’s important that you eat vegetables.” Here comas (not comes) signals that it’s important but not certain that you do it.

See the pattern? Here’s a quick visual table for three verbs (one of each type) in the present subjunctive:

| Subject | -AR (hablar) | -ER (tener) | -IR (vivir) |

| yo | hable | tenga | viva |

| tú | hables | tengas | vivas |

| él/ella/Ud. | hable | tenga | viva |

| nosotros | hablemos | tengamos | vivamos |

| vosotros* | habléis | tengáis | viváis |

| ellos/Uds. | hablen | tengan | vivan |

*Keep in mind that the “vosotros/vosotras” form is used almost exclusively in Spain (and a few pockets like Equatorial Guinea). In most of Latin America, speakers use ustedes for all plural “you,” so you can safely skip the “vosotros” line if you’re focused on Latin-American Spanish.

What about irregulars? (Meet the DISHES)

Generally, Spanish subjunctive forms follow the yo-form rule.

If a verb has an irregular yo form in the present (like tengo, digo, conozco), that irregularity carries into the subjunctive stem.

For example:

- tener (to have) → yo tengo → teng--, so we get tenga, tengas, …

- decir (to say) → yo digo → dig--, so diga, digas, …

- venir (to come) → yo vengo → veng-, so venga, vengas, …

The good news: only a handful of verbs are truly irregular in the present subjunctive (meaning they don’t just follow their yo-form stem).

In fact, there are 6 superstar irregular verbs you should memorize. They are so famous they have a nickname: “DISHES” verbs (dar, ir, saber, haber, estar, ser).

| Person (subject) | dar | ir | saber | haber | estar | ser |

| yo | dé | vaya | sepa | haya | esté | sea |

| tú | des | vayas | sepas | hayas | estés | seas |

| él/ella/usted | dé | vaya | sepa | haya | esté | sea |

| nosotros/nosotras | demos | vayamos | sepamos | hayamos | estemos | seamos |

| vosotros/vosotras | deis | vayáis | sepáis | hayáis | estéis | seáis |

| ellos/ellas/ustedes | den | vayan | sepan | hayan | estén | sean |

Memorize DISHES, and you’ll have the worst offenders covered.

For a fun mental image, imagine these six verbs as unruly dishes in a sink that you have to remember to wash (they just won’t clean themselves by the normal rules!).

So, forming the present subjunctive is as easy as 1-2-3: yo form, drop “o”, add swapped endings. Not so scary after all, right?

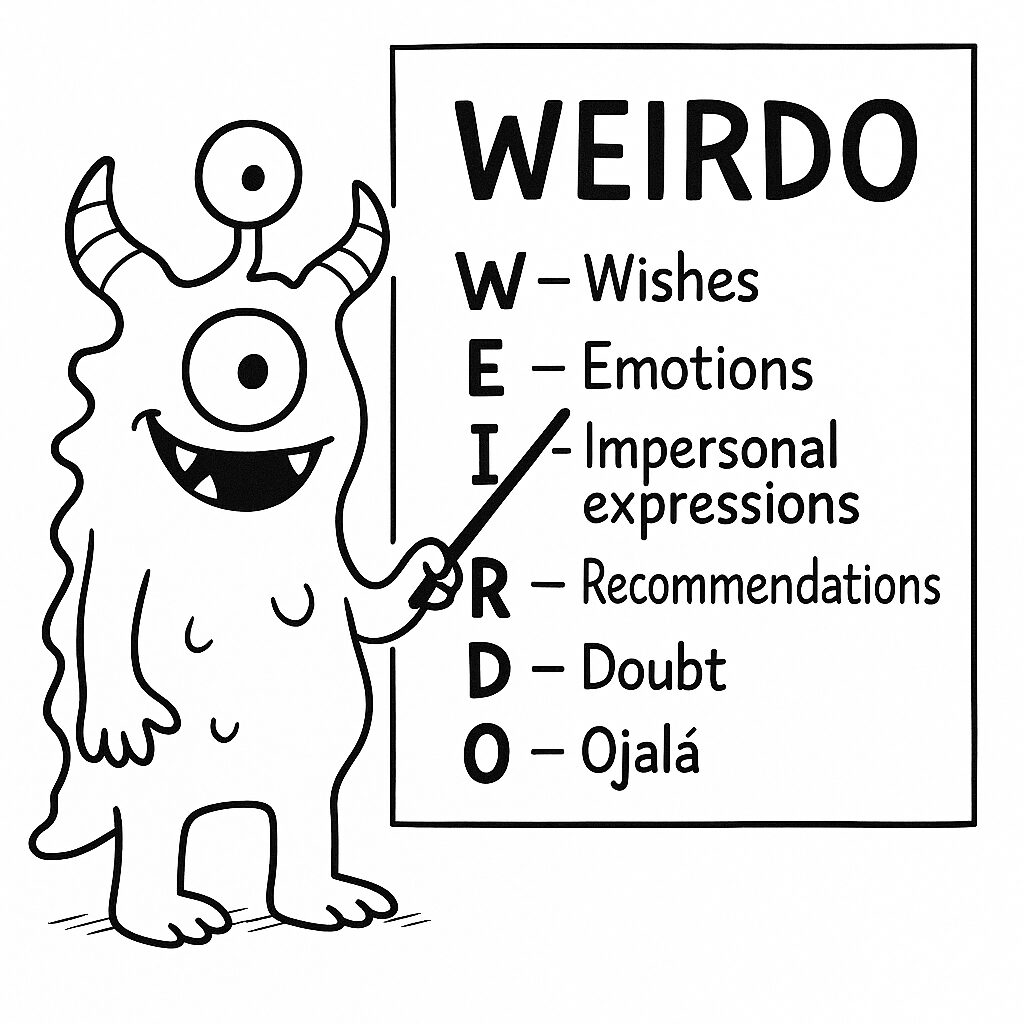

When to use the present subjunctive (WEIRDO)

Think of them as two parts:

- Part 1 (before “que”): shows the feeling, wish, doubt, or necessity.

- Part 2 (after “que”): shows the action and uses the present subjunctive.

A handy acronym is WEIRDO:

| Letter | Trigger type | Spanish starters | English meaning |

| W | Wishes/wants | quiero que, espero que, ojalá | “I want (that)”, “I hope (that)”, “hopefully / God willing” |

| E | Emotions | me alegra que, siento que, me sorprende que | “it makes me happy that / I’m glad that”, “I’m sorry that”, “it surprises me that” |

| I | Impersonal expressions | es bueno que, es posible que, es necesario que | “it’s good that”, “it’s possible that”, “it’s necessary that” |

| R | Recommendations/requests | te recomiendo que, pido que, sugiero que | “I recommend that you…”, “I ask that…”, “I suggest that…” |

| D | Doubt/denial | dudo que, no creo que, niego que | “I doubt that “, “I don’t think that “, “I deny that” |

| O | Ojalá (one-word hope) | ojalá (que) | “hopefully / I hope (that)” |

Below are short examples. The subjunctive verb is bold.

W – Wishes and wants

Quiero que tú vengas. – I want you to come.

Deseamos que ella tenga éxito. – We wish she has success.

E – Emotions

Me alegra que haya sol. – I’m happy there is sun.

Lamento que no puedas venir. – I’m sorry you can’t come.

I – Impersonal expressions

Es importante que los niños duerman. – It’s important that the kids sleep.

Es posible que él llegue tarde. – It’s possible he arrives late.

R – Recommendations and requests

Te recomiendo que estudies más. – I recommend that you study more.

Nos piden que apaguemos los teléfonos. – They ask us to turn off our phones.

D – Doubt and denial

Dudo que María esté lista. – I doubt María is ready.

No creo que esto sea verdad. – I don’t think this is true.

O – Ojalá

¡Ojalá llueva café! – Hopefully it rains coffee!

¡Ojalá que mañana salga el sol! – Hopefully the sun comes out tomorrow!

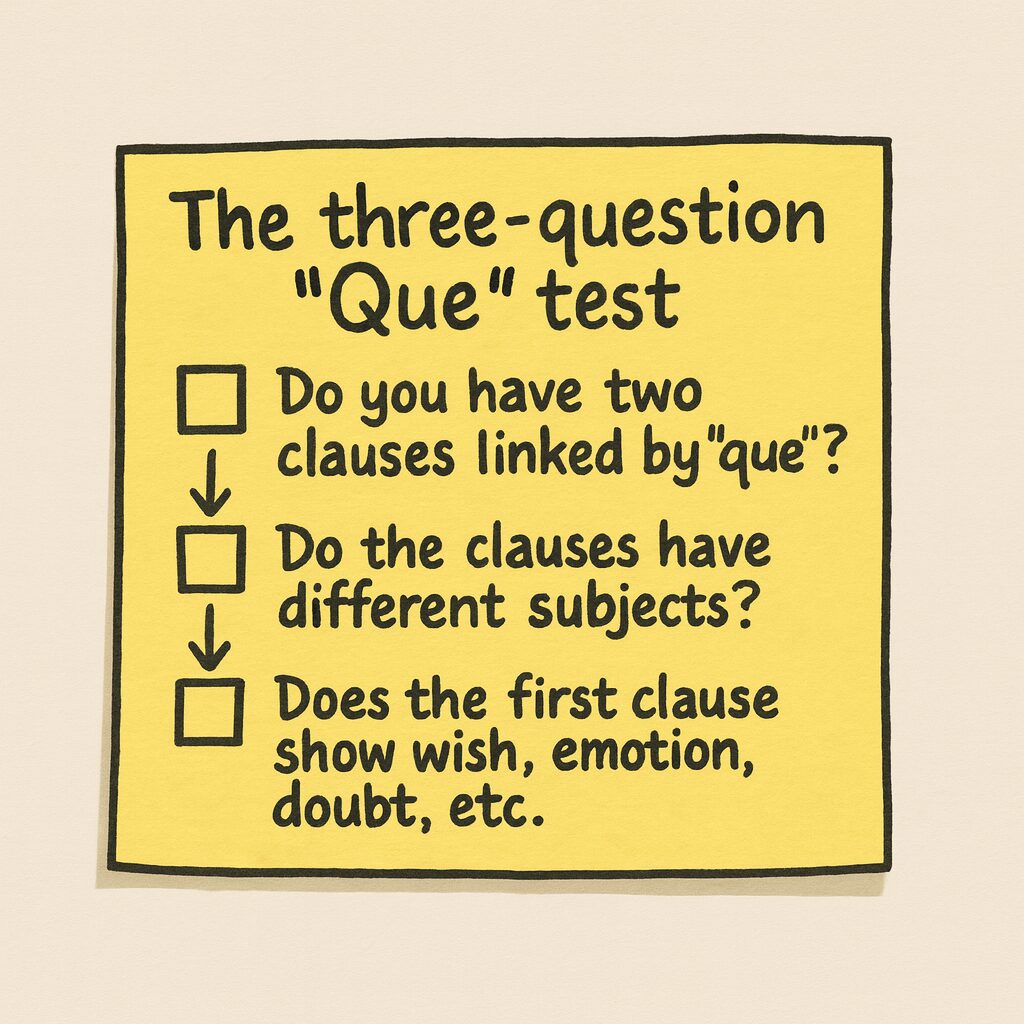

Checklist: Subjunctive or indicative?

Ask yourself these three quick questions:

- Is there a “que” joining two parts of the sentence?

Example: Quiero que vengas. - Do the two parts have different subjects?

Example: I want you to come. (yo ≠ tú) - Does the first part show a wish, feeling, doubt, hope, or necessity?

Examples: Quiero…, Espero…, Dudo…, Me alegra…, Es necesario…

How to decide

- If you answered “yes” to all three, use the subjunctive in the second part.

Example: Quiero que vengas. / Es importante que estudien. - If any box is “no,” you probably need the indicative (or just an infinitive if the subject is the same).

Example: Quiero estudiar. (same subject → no “que”)

Conclusion

The present subjunctive isn’t a grammar monster; it’s simply Spanish’s way to mark subjectivity.

Remember:

- Forming it = yo form → drop “-o” → opposite endings.

- Using it = two clauses + different subjects + WEIRDO trigger.

- Irregulars = memorize DISHES; others behave.

With a bit of practice, you’ll drop sentences like “Espero que tengas un gran día” without breaking a sweat.